AI Note-Taking Tools at Work: Powerful New Capabilities, Used Thoughtfully

Estimated reading time: ~7 minutes

I’ll start with a confession: I’m probably a bit late to discovering AI note-taking tools. Over the past several months, though, I started hearing more about AI note-taking applications like Granola.ai, Otter.ai, Fireflies.ai, Fathom.ai, and similar tools. Colleagues and clients mentioned how these apps can listen to meetings, generate detailed summaries, and create searchable records without anyone having to take notes manually.

At first glance, it’s hard not to be impressed. As someone who has practiced employment law for more than twenty years, I’ve sat through more meetings, calls, interviews, and training sessions than I can count. The idea of a tool that can reliably capture what was said, organize it, and make it easy to reference later is genuinely exciting. From a productivity standpoint, these tools feel like a giant leap forward.

Part of what makes this category so compelling is that different tools are positioning themselves for slightly different use cases. Platforms like Otter.ai and Fireflies.ai emphasize real-time transcription, searchable meeting histories, and integrations with common video-conferencing tools, making them attractive for recurring team meetings and collaborative workflows. Fathom.ai tends to market itself toward video meetings, highlighting automated summaries, action items, and follow-up notes designed to reduce post-meeting administrative work. Granola.ai, by contrast, appears to focus more deliberately on structured settings such as seminars, lectures, and group sessions, where the goal is capturing substance rather than managing back-and-forth discussion. While the feature sets overlap, the common thread is the same: these tools promise to turn spoken conversations into organized, retrievable records with far less friction than traditional note-taking.

It is also worth noting that AI note-taking and meeting-summary features are no longer limited to niche startups. Zoom now offers integrated AI transcription and summary tools through Zoom AI Companion, and Microsoft Teams has similar capabilities through Microsoft Copilot. For many employers, these features are already embedded in platforms they use every day, sometimes enabled by default or activated at the administrative level. The growing integration of AI note-taking into mainstream enterprise software underscores that this is not a fringe technology trend, but a rapidly normalizing workplace capability—one that brings both meaningful efficiency gains and important compliance considerations.

Once I started thinking about these tools and how they are being deployed in real workplaces, I also began to see how useful they could be in my line of work and for HR professionals when used correctly.

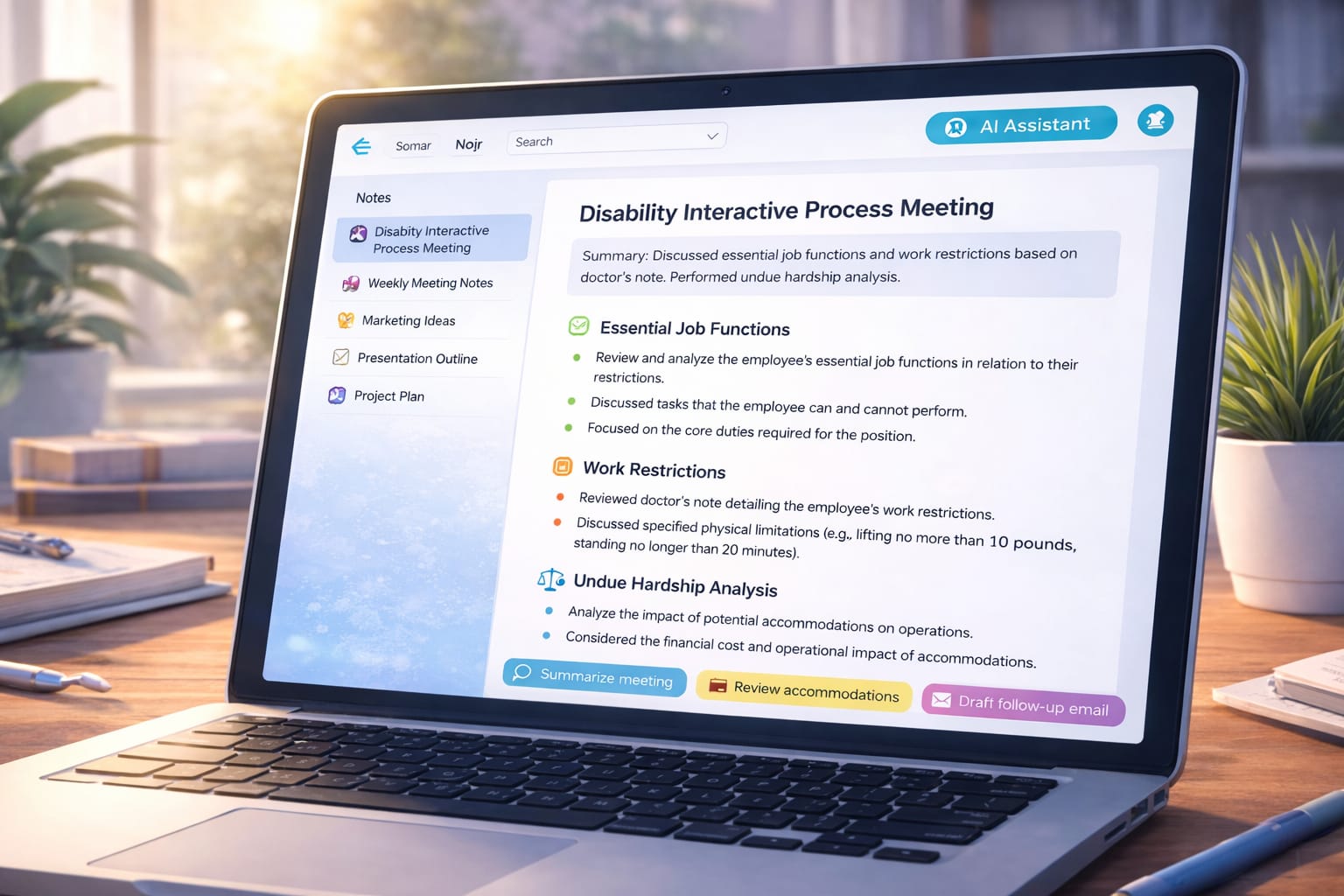

One obvious example is the disability interactive process. Employers are required to engage in a good-faith, interactive dialogue with employees who request accommodation, and disputes can arise later about what was discussed, what options were considered, and what agreements were reached. An AI-assisted meeting summary—reviewed and corrected by a human—can help create a contemporaneous record showing that the employer engaged in the required process and documenting functional limitations, accommodation options, and next steps.

These tools can also be valuable in coaching, counseling, or disciplinary meetings. Capturing what performance expectations were discussed, identifying specific deficiencies with examples, clarifying what acceptable performance looks like going forward, and documenting the consequences if improvement does not occur can all be critical if decisions are later challenged. Used thoughtfully, AI-generated notes can support clearer communication and better documentation than hurried handwritten summaries created after the fact.

A third promising use case is training. Employers are increasingly expected not just to have compliant policies, but to show that training actually occurred and what topics were covered. AI-generated summaries of leadership or employee training sessions—such as wage-and-hour compliance refreshers or policy reviews—can help demonstrate that the employer took reasonable steps to educate its workforce and reinforce compliance obligations.

A fourth and particularly important use case is workplace investigations and fact-finding meetings. When employers investigate employee complaints, they must accurately capture the substance of the complaint itself, as well as the details provided by percipient witnesses and the accused employee. Investigations often hinge on credibility, consistency, and specificity, and memories can fade or shift over time. AI-assisted notes, once carefully reviewed for accuracy, can help preserve what was actually said during interviews and meetings, supporting a fair, thorough, and well-documented investigative process.

So there is real reason to be excited about these tools. But, as is often the case with new technology, the benefits depend heavily on how and where the tools are used. That’s where some legal guardrails come into play.

One key issue under California law is recording consent. Penal Code section 632 generally prohibits recording a confidential communication without the consent of all parties, and section 632.7 applies similar rules to telephone calls. A confidential communication is one carried on in circumstances where participants reasonably expect it will not be overheard or recorded. Many workplace conversations—especially one-on-one meetings, management discussions, and calls involving performance, discipline, or complaints—fall into that category.

Although AI note-taking apps are often described as “note-taking” tools, most operate by capturing live audio and converting spoken words into a verbatim or near-verbatim transcript. Even if the underlying audio file is not saved or shared, the transcript itself preserves the substance of the conversation for later review. While courts have not yet squarely addressed AI transcription tools under these statutes, the fact that these applications capture spoken communications verbatim and preserve them for later review makes it easy to envision a court concluding that their use constitutes a “recording” within the meaning of California’s privacy statutes.

Context matters here. Some platforms, including Granola.ai, emphasize use cases such as seminars, lectures, or large group meetings where there is little or no reasonable expectation of privacy. In those settings, risk is generally much lower. The risk increases when these tools are used in private in-person meetings without notice, or in phone or video calls without explicit consent.

From a practical standpoint, that means employers should think carefully about knowledge versus consent. For in-person meetings, clear advance notice that AI note-taking will be used can eliminate any reasonable expectation of privacy. For phone or remote meetings, explicit consent from all participants—ideally documented—is the safer approach.

Another important consideration is accuracy. I recently tested one of these tools in a non-private meeting and found it to be mostly accurate—but not perfect. There were a few substantive errors that mattered. That experience reinforced a key point: AI-generated notes should be treated as drafts, not final business records. Before they are filed, shared, or relied upon, someone needs to review them carefully for accuracy and completeness, making corrections as necessary. Human validation remains essential.

Beyond recording laws, these tools also raise questions about document disclosure. California Labor Code section 1198.5 gives employees the right to inspect and copy personnel records relating to performance or any grievance concerning the employee. These requests often arrive before litigation and are frequently a prelude to it.

If AI tools are used to transcribe or summarize meetings involving complaints, investigations, or disciplinary discussions, employees may argue that those materials fall within the scope of records subject to production. This is an emerging area of law, and courts have not yet provided clear answers about how AI-generated transcripts or summaries fit into existing statutes. Still, their very existence may create new points of contention that employers should anticipate.

Similar issues can arise in civil discovery. Verbatim transcripts and AI-generated summaries may be discoverable, may expand preservation obligations, and may become evidence in ways employers did not originally intend. Technology doesn’t just document meetings—it can change the evidentiary landscape.

None of this means employers should shy away from AI note-taking tools. Used thoughtfully, they can enhance communication, improve documentation, and support compliance efforts. The key is to deploy them deliberately, with clear internal guidelines, appropriate notice or consent, and a firm practice of human review.

In my experience, new technology rarely creates legal problems on its own. The problems usually arise when tools are adopted informally, without fully considering how existing laws apply. AI note-taking is no exception. With the right approach, these tools can be a powerful addition to an employer’s compliance and productivity toolkit rather than a source of unintended risk.